How do antibodies against PfRIPR stop erythrocyte invasion in malaria?

The PfPCRCR complex is required for the deadliest malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum to get inside our blood cells. Indeed, all five components of this protein complex are targets of antibodies that can block erythrocyte invasion. But how do these antibodies work and how can knowing how they work help us to design improved malaria vaccines?

Our previous studies have revealed in detail how antibodies that target PfRH5 and PfCyRPA work and this insight is already guiding our development of improved vaccine immunogens based on these molecules. However, the PfRIPR component is a mystery. While we have revealed the structure of PfRIPR and showed that it lies at the centre of a bridge which links the parasite and erythrocyte during invasion (Farrell et al 2024), we do not know how PfRIPR functions or how antibodies block its function.

To answer these questions, we teamed up with Andrew Cooper and Joshua Tan at NIAID to study PfRIPR-targeting antibodies. Andrew and Joshua are isolating antibodies which bind to PfPCRCR components from Malian volunteers who have previously experienced natural malaria infections. We combined three of their antibodies with a previously identified mouse-derived antibody which can block erythrocyte invasion, generating a small antibody panel.

Structural studies of these antibodies, led by Brendan Farrell, revealed many fascinating insights into how PfRIPR works and how we might stop it!

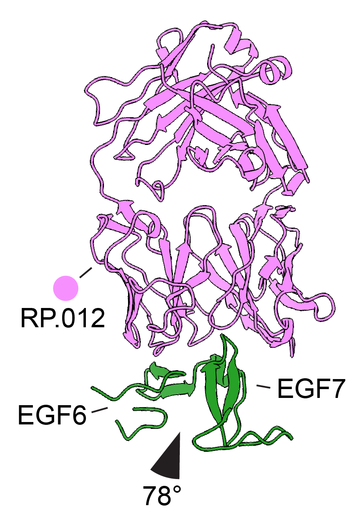

First, we showed that PfRIPR is flexible and contains at least two hinges in the part of PfRIPR which bridges from the erythrocyte to the parasite. Remarkably the most effective growth-inhibitory antibody holds one of these hinges in a specific conformation. This suggests that hinge movement in PfRIPR is required for it to carry out its function in erythrocyte invasion and that antibodies targeting the hinge can block the invasion mechanism.

Second, inhibitory antibodies target a region of PfRIPR mid-way between the erythrocyte and parasite membranes consisting of four EGF domains (EGF5-8). A vaccine (R78C) has already progressed into clinical trials which contains part of this region of PfRIPR. Our findings caution against rushing into including this part of PfRIPR in a vaccine. The epitope for the best PfRIPR-targeting antibody is missing from R78C and we also show that antibodies targeting this region of PfRIPR can interfere with, or antagonise, the function of the most inhibitory antibodies. Development of PfRIPR-based immunogens requires more thought.

Finally, we find a novel mechanism of antibody synergy, in which two antibodies make one another better! We show that growth inhibitory antibodies which bind to the EGF5-8 region in the centre of PfRIPR synergise with antibodies which bind to the C-terminal domain of PfRIPR, close to the parasite membrane. These antibody binding sites lie far apart and so we propose that they must come close together during the invasion process, perhaps with flexibility at one of the PfRIPR hinges allowing compaction of PfRIPR. Blocking these shape changes, using antibodies which bind to different sites, can stop the parasite.

This study therefore shows that PfRIPR is a complex and dynamic molecule, forming a flexible bridge which links parasite and erythrocyte during the essential process of erythrocyte invasion. Antibodies which interfere with its flexibility, either by locking its hinges or by getting in the way of its shape changes, can prevent PfRIPR function and erythrocyte invasion. The challenge now is how we design a vaccine which causes our bodies to make this repertoire of effective antibodies!

Farrell, B., Cooper, A.J.R., Butkeviciute, E., Wang, L.T., Egerton-Warburton, W., Tan, J. and Higgins, M.K. (2026) Dynamic hinge-motion of PfRIPR revealed by malaria invasion inhibitory antibodies. BioRXIV https://doi.org/10.64898/2026.01.14.699498